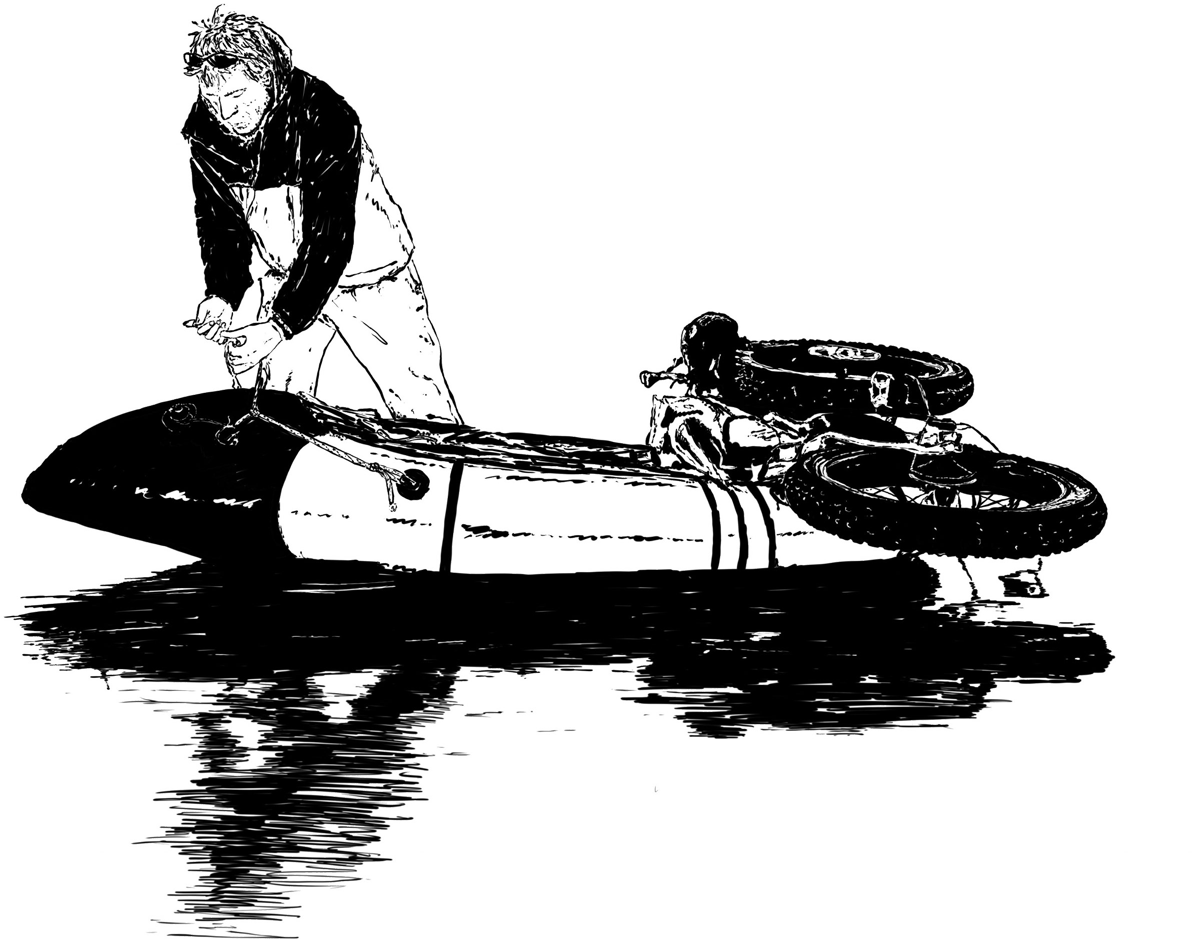

Story by Lizzy Scully, photos and captions by Dave Gray and John Evingson, an excerpt from the history section of The Bikeraft Guide.

Plenty of accounts of the history of fatbikes exist on the internet. But none address the true history of fatbikes or the fact that they developed hand-in-hand with packrafts. In this excerpt from The Bikeraft Guide, we reveal the truth 😉

WHICH CAME 1ST, THE FATBIKE OR THE PACKRAFT? THE REAL HISTORY OF FATBIKES

No one interviewed for this book could identify for sure which technological concept blossomed first, the fatbike or the packraft (or bike bags, for that matter). They almost appeared to morph into the “sport” of bikerafting simultaneously.

“It was this lust for the ability to go from point A to point B in the straightest line,” says Dave Gray, one of the early adopters and developers of the fatbike. “And both those tools for exploration lent themselves to each other. And obviously you could carry a boat on a bike and a bike on a boat. So why wouldn’t you when you’re traveling through those places without roads. Places without roads generally have water bodies that you have to cross. And you can either go around or go over them. And it’s the same with soft terrain (snow, sand, etc). You can either ride around or go over it.”

THE IDITABIKE: THE TOUGHEST MOUNTAIN BIKE RACE IN THE WORLD

The desire to cycle soft terrain inspired the very first Alaskan adventure racers to start envisioning fatter-tired bikes for the Iditabike. This was a key moment in the history of fatbikes and their development.

Around the same time Alaskans were exploring fatter tires, a New Mexico-based mountain bike guide, Ray Molina, wanted to take clients on the sandy trails and landscapes of Mexico and New Mexico.

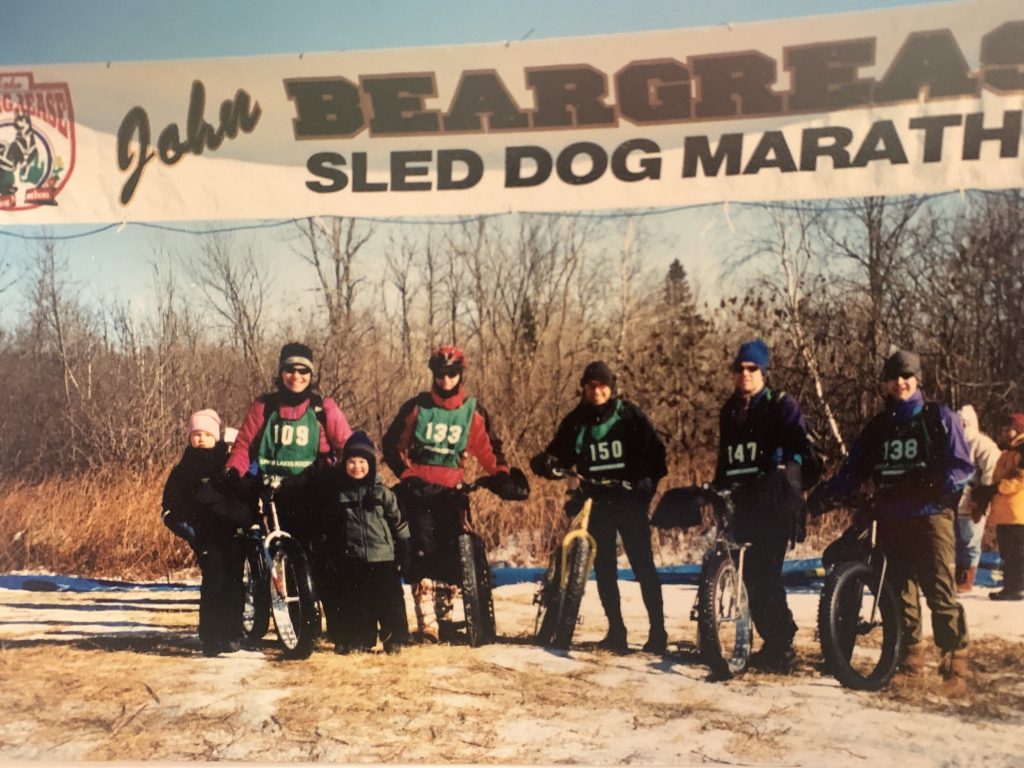

According to a Charlie Kelly’s blog post, “The Brotherhood of Pain: The First Iditabike,” in 1986, the founder of the original 1971 Iditarod, Joe Redington Sr., invited the Mountain Bikers of Alaska (MBA) to race mountain bikes. They would ride the 210-mile ski-race course that follows the lditarod Trail out of Knik for a hundred miles and return And they’d do this in the winter, leaving the day after the dogsled race.

“It was the latest version of extreme sporting challenges loosely patterned after the 1100-mile Iditarod sled dog race,” he explains. MBA accepted the challenge.

BLIZZARDS, BELOW ZERO & DEEP POWDER

“In a state known for extremes — of cold, of distance and of athletic challenges — the local mountain bikers have created a challenge that has been billed as ‘The Toughest Mountain Bike Race in the World,’” Charlie writes. “Considering that the distance is four times that of the race which had previously held that unofficial title, that the race is conducted in deep pow, and that the weather possibilities include blizzards and temperatures far below zero, no one is likely to argue the point.”

Because of this, organizers thought ten people max might enter the race. Turns out 20 men and six women entered and 13 finished. There were nine men and two women (one in 6th place). “According to the race rules, riders had to carry, in addition to the usual tools, survival gear for minus-20 degree nights and blizzards, food, stove, flares, riding lights, first aid kit, and so on-the same gear the mushers were expected to have on their sleds…” writes Charlie Kelly. They carried gear either by towing sleds (slower) or by going minimalist and packing equipment bikepacking style (more efficient). And they used variations of hand-modified studded tires.

COWARDS WON'T SHOW, AND THE WEAK WILL DIE: WHEN FAT-TIRES BECAME A NECESSITY

It also turns out that due to dog sled brakes churning up the snow and high temps, the trail transformed into an unrideable mush of soft snow.

“Conditions along the trail range[d] from rideable frozen crust — the result of daily freeze-thaw cycles — to a mélange of soft snow, glare ice, and liquid water overflow,” writes Nicholas Carman in a February 2018 issue of Adventure Cycling. “Harsh conditions, and lots of walking alongside a bike in the snow challenged riders to improve their equipment for next year. A wider tire footprint was essential.”

According to Nick Heil in a 2015 Outside Online article, word spread quickly about the epic nature of the bike race. And it began to attract an elite field of participants, such as Mountain Bike Hall of Famer John Stamstad and Mike Curiak, a 24-hour bike-racing champion.

“A popular slogan at the time was ‘Cowards won’t show, and the weak will die,’” Nick writes. “The race also prompted some wild innovation.” That innovation translated into tinkerers building fatter tires in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s.

THE TINKERERS START DEVELOPING FATTER TIRES

Steve Baker of Icicle Bicycle’s may have been one of the first to begin experimenting with welded tire rims. Mounting two tires side by side, he created a double-wide tire measuring 4.4. He even welding a frame to fit the wheels, explains Lauren Constantini, in “Being Fat: The History of Fat Biking” (January 2018). He aspired to achieve more contact on snowy terrain in order to better traverse Alaska in the winter.

Around the same time in 1989, Bjorn Olson reports on his blog article, “Pay it Forward,” that Roger Cowels and three other cyclists were the first people to ride the Iditarod Trail from Anchorage to Nome.

“Roger rode the trail on a custom, four wheel bike of his own design,” Olson writes. “After that trip, Roger went back to the drawing board and with the help of Phil Wood and Anchorage welder Steve Baker, they came up with ‘Big Foot’, a six tired winter bike.”

Just a year later in 1990, adds Wyatt Hrudka, Alaskan Simon Rowaker built his own, inspired by Baker. “[He] decided to make a dedicated 44mm wide rim called the Snowcat, which eventually became the go-to rim during the early 90s,” he writes at wyattbikes.com. “They weren’t quite the size of modern fat bike rims of today. But they were the largest production rim of that time and highly sought after by adventure cyclists.”

AND THE HISTORY OF FATBIKES TAKES A TURN: RAY'S REMOLINA RIMS & JOHN'S FATBIKE FRAMES

Around the same time, John Evingson told us in an October 2020 interview that Ray started building 3.1” (79mm) “Remolina” rims and 3.5” (89mm) “Chevron” tires. His goal was to take his tour business clients riding to the sandy arroyos and dunes of Mexico and New Mexico. In 1999, he brought his rims and tires to Interbike. There, he met Mark Groenewald, owner of Wildfire Designs Bicycles in Palmer, Alaska, and John, owner of HydraCare, a company that made cleaning and drying kits to maintain hydration bladders.

Mark and John collaborated. Mark did the drawings and John utilized his welding skills, iron work experience and engineering background to build the first five “fat bike” frames. Eventually Groenewald, with John’s blessings, found a bike builder on the East Coast and had some of his own bikes made.

GOING AROUND THE CYCLING INDUSTRY

The cycling industry’s bikes at the time wouldn’t accommodate the big fat tires, says John. “So Ray had to do something really weird to make it work (the rear tire was offset 3/8ths of an inch).” But John knew he could fix the problem. So, he bought some rims and tires, returned to Alaska and built a bike for his wife Kathie, himself, Dan Bull, who ran Iditasport, and two others. And they were all specifically geared for that 2000 winter Iditasport. Thus, he made them on a super light, stainless steel road bike frame, with integrated racks.

“What I really did first was correct Ray’s design so that it was more applicable to actually riding. And I brought them to Alaska to use them in the snow and to provide more float for the snow,” John says. “I went a little bit overboard,” he adds, making them super specific to winter racing bikes. “But, it was a hit that year. It did really well.”

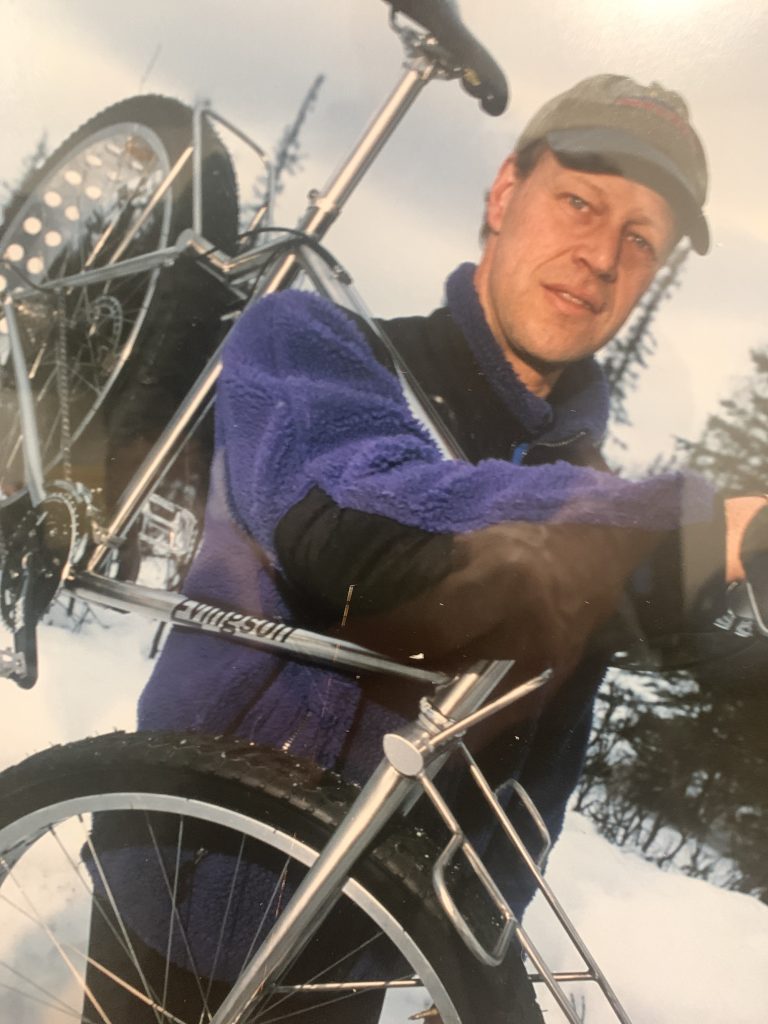

QUALITY BICYCLE PRODUCTS & DAVE GRAY: FATTIES FIT FINE

Later that summer John moved back to Minnesota. There, he got in touch with Dave Gray of Surly and Quality Bicycle Products. And he told them about his new fat bikes.

“I knew I couldn’t do anything with them,” he explains. “I’ll never forget that phone call back. Dave asked, ‘we’re interested in doing this. Will we be stepping on your toes if we make these bikes?’ I was like, ‘well, give me some free parts and credit in your catalog, and they did that first year. And then they made the Pugsley.”

“John was the person who was instrumental in Surly getting into fat bikes,” says Dave. And, by the time he contacted QBP and Dave, the supplies of Remolina products had run dry.

“Basically there was a desert of product, So John came to Surly one day with his fat bikes, and we had a parking lot meeting. We bounced around on these clown bikes, which is what my friend Charlie Farrow called them initially, ‘until he came over to the dark side and finally succumbed to the need/desire to obtain one for himself,” Dave explains. He had tires. But he needed rims and asked QBP if they’d be interested in making rims.

“We were like, well that’s pretty cool,” Dave remembers of riding bikes on the “swampy mountain bike loop” at John’s parent’s farm. “The mantra of Surly was, ‘Fatties Fit Fine,’ which we put on the chainstays of our bikes. So we knew if we made wide rims that they would actually fit some of our bikes.”

THE PUGSLEY PROJECT

In one of the most significant developments of the history of fatbikes, QBP agreed to make the rims. And within a year, they decided they might as well make a tire and frame as well.

“That’s how the Pugsley project started and the Endomorph tire. People say Surly was the first production fat bike brand. It was the first mass production fat bike brand. But Ray should be credited as doing the first production stuff.” Followed by John making the first full production bikes.

DAVE’S PASSION PROJECT

Dave led the design work on the newest versions of fat bikes, with help from two engineers. But it was basically his project—the tire, the rim and the frame—because he was the most passionate about it. He had cycled winters since 1991. And he was always looking for a “holy grail” of a better way of riding through Minnesota’s winters.

“That was my incentive. I wanted to go more places, ride over softer ground and looser soil. And what it came down to is I wanted to ride more than pushing my bike. I was always looking for that next fattest tire. And I had welded rims together and sewed tires together, the same thing all those back shed tinkerers had done.”

AND THE HISTORY OF FATBIKES CONTINUES... A NEW KIND OF ADVENTURE RACING

Dave loves the fact that fat biking is so multi-faceted now, with numerous companies producing them and people in all walks of life using them. People who felt mountain biking was sketchy love the stability of the fat tires, while explorers still use them to go places they couldn’t go with other bikes or by any other means.

John agrees, adding, fat bikes really bring people together to enjoy the trails. “The fat tire bike took away the competition of cycling. It’s a lazy way to ride. It made it easier for people to accept a slower pace. We’re just riding graciously and fun and not trying to go faster. It’s amazing how big the user group has become because of the fat tire bike.”

And finally, adds Dave, fat bikes opened up this whole new segment of adventure racing, especially the kind that incorporated packrafts. But that’s not all…

Stay tuned for the next history excerpt from The Bikeraft Guide, “Live To Ride, Ride To Die… Or Not? – The 2000s.”

In addition to the history of fatbikes, we have numerous excerpts of The Bikeraft Guide both on this blog and at Four Corners Guides. Check them out: